All Aboard the Reading Train

Equity and Learning To Read: Starting Together From Common Ground and Following a Purposeful Pathway

Written by Molly Branson Thayer

There is an entire engineering system that needs to be in place to learn to read. Recently I was re-reading one of my favorite children’s books, and one of my students' favorites, Freight Train by acclaimed author Donald Crews. In this story, a train made up of colorful train cars zooms along tracks. It is propelled by a powerful engine up front, a caboose in the back, and it carries all the people responsible for making that train go.

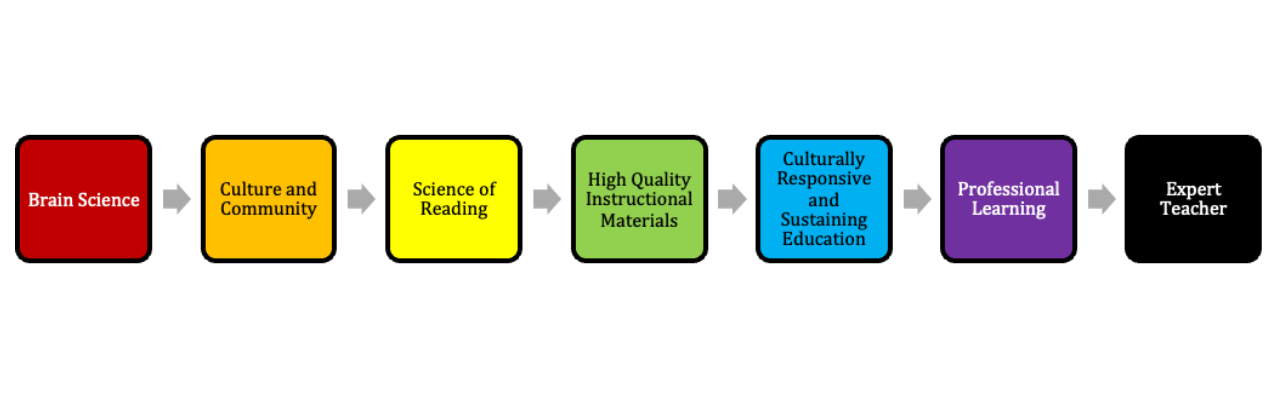

Page by page, the train moves on the track, and as it goes the colorful train cars blend together and create a rainbow—a rush of colors running together until it’s going… going… gone! This isn’t too far off from how we at Teaching Lab think of reading development. Each train car represents a critical link in the foundation of learning to read.

In the back, there is each child, their family shoring up the back in the caboose. Then come the train cars: brain science - a red car, culture and community - an orange car, the science of reading - a yellow car, high-quality instructional materials - a green car, culturally responsive-sustaining education - a blue car, professional learning for teachers - a purple car, and, of course, the teacher with her expertise - the black engine up front. Put all of these cars together, and this reading train is all ready to go!

Over the course of the next few weeks, we will journey through this blog series inside each of these cars to unpack each component of reading development. We will not only reveal why each car is critical in learning to read, but we will culminate this series in a handy “how-to” supporting you to implement the lessons learned from each car and their links whether you are a parent, a teacher, a childcare provider, or a literacy specialist.

All Aboard!

Today, we are starting with the red car, or brain science.

***

We’ve learned so much in the past decade about how to communicate best with babies and children. For instance, we know that children like to be spoken to in high-pitched tones. In order for a baby to connect, get close—preferably eight-to-ten inches from that baby’s face.

This seems pretty natural and instinctual, really—can you picture the scene? A mother gets down close to their baby and says in a high-pitched voice, “ah-goochie, goochie, goo.” Babies register that and begin to babble back. And that babble—it’s actually in the vowel sounds of the language spoken to them. So, native English-speaking babies will say, “ahhhhh,” “ooooh,” and “oh.” They are practicing English, and as we all know, practice makes perfect.

This is why the birth-to-three window is so critical. This is why there is a nationwide call to pay early childcare workers more. These brain scientists care for our babies every day, and they are incredibly gifted at building safe, comforting relationships with babies, engaging in face-to-face baby talk, and offering opportunities for back-and-forth ‘conversations,’ critical for language and cognitive development.

What we now know about the brain and how it works, especially in early development, helps us understand how critical the earliest caregivers are to each baby and how babies become so immersed in their culture and community. Brain science tells us that early brain development affects the course of our lives. These first environments remain with children into adulthood. For example, in a baby’s first year, the parts of their brains that differentiate vocal sounds, like how /r/, /a/, and /k/ sound in English, are at attention. Babies register these sounds and, like statisticians, take note of frequently-used sounds.

After the first year, they are so good at recognizing English language sounds they ‘tune out’ non-English sounds, like those that come from speaking French or Mandarin.

Their pathways for recognizing, and eventually speaking, English grow deeper, and their ability to tune into other languages fades. Early caregivers of babies have more influence on creating new pathways in a baby’s brain than just about anyone trying to do the same later on.

At Teaching Lab we understand these early connections made in each child’s brain, and we honor them by attending to each child’s unique way of being, thinking, and expressing themselves. We know that with brains stimulated, little infants become happy, talkative toddlers who then become curious little kids. Through this time period, they develop within their community and become a part of the culture around them. With our understanding of the critical role brain science plays in early childhood and how our earliest caregivers are brain scientists, we can climb aboard the next car in the Reading Train.

Enter this orange car and you’ll notice how brain science links to culture and community. Starting at this very young age, children learn to develop schema, or knowledge about the world around them. Think of it as a combination of brain architecture and culture that establishes pathways in an individual’s brain. In other words, they learn about the world through their experiences in it.

Repeated experiences help a child develop details, expectations, thought patterns, and a certain level of comfort from the familiarity. For instance, a child may begin to understand how food gets to their table by accompanying a parent to the grocery store, bringing the groceries home and putting them away, and then getting that food out again and preparing it for a meal. Through repeated experiences accompanying a parent to the grocery store, a child develops a rich schema for this experience that includes vocabulary used by the parent like ‘bus stop’ or ‘parking lot,’ ‘aisle,’ and ‘check-out.’ How the parents shop, what they choose to talk about in the grocery store, if they sing along to music in the car, listen to the news, or ride a bus and look out the window or read a paper are all a part of the culture that is passed down from adult to child and represented in the child’s mind.

Schema represents the words, language, thoughts, and ideas associated with the experiences one is exposed to. Schema is the brain's way of categorizing content (think of graphic organizers) so it can be accessed as needed. Each child has a unique schema, or knowledge and vocabulary, based on their early experiences, and their schema grows as they grow and have new experiences and learn new things.

At around three years old, children begin their journey into imaginary play. They bring their early experiences and ways of being in the world with them. Try to picture a little three-year-old child playing ‘house’ at home or in the preschool area with the pretend kitchen, crib, and babydoll or a different child playing with blocks or in the block area:

Scenario 1

Child 1: I am the mom and this is my baby. We are going to the grocery store.

Child 2: I am the big sister, and I am going to bring my purse and my phone.

Child1: I need a phone too.

Child 2: Here, you can use this. We can both use these as our phones.

Child 3: I want to play. Can I be the dad?

Child 1: No, you can be the big brother.

Child 3: Okay, but I am the one that gets to drive to the store.

Child 2: Okay.

Scenario 2

Child 1: I am building a tower.

Child 2: Okay, I am going to make a bridge to the tower and come attack you.

Child 1: I am the hulk, and if you try to destroy my tower, I turn into the hulk and fight you.

Child 3: I am flying a fighter jet and I am going to attack from above. This block is my plane.

Child 2: Okay, we are on the same team.

Through play, young speakers bring their schema and reenact experiences they have had or seen. Through play, they are directing the talk and engaging in communication that interests them and teaches them how to be in the world. They create a setting, build characters, and edit and revise based on input from others. This early play experience is the beginning of narrative composition, a structure for language that begins as soon as children begin to speak. Starting with the beginning of language production at 18 months, our earliest sentences include a subject and a verb, like “Daddy go?” In other words, sentences become a narrative about who is doing what. As toddlers grow, so does their sophistication with narrative structure, especially around personal experiences.

They are able to tell their caregiver what they did, like, “I went park… and slide.” Eventually, typically by three years old, they become great at sharing narrative language and using the narrative structure when talking to their friends and family. They go beyond talking about themselves and what they did or want and begin to imagine, create, and compose narratives using what they know about the world to explain, play, and pretend.

All children have experiences that build their background and vocabulary knowledge—this was outlined in Part 1 of this blog series. They then use this knowledge during interactions with others, including play, to practice language and language structures, composing narratives and storylines with settings, characters, and events, like in the two scenarios above. The skills developed in these early years are only part of the foundation of learning to read. Of course there is much more, and we will unpack it all. This week we wanted to kick around in the red and orange cars to better understand how brain science connects language, culture, and thought.

So, think of Schema as a combination of ideas and words, or sketches and dreams. This is the stage where children are sketching out ideas and ways of being and also dreaming themselves into the world. It is important for childhood development, but it is deeply rooted in reading development and a critical link from brain science to the science of reading—the next train car ahead.

Wishing you a week of goochie-goochie-goos, big dreams, and glorious sketches,

Molly

Molly Branson Thayer, Ed.D. is the Sr. Director of the Early Literacy Innovation Lab at Teaching Lab and leads the early literacy strategic vision, ensuring that Teaching Lab is a trusted voice in early literacy and plays a critical role in supporting all educators to develop strong readers across the country.